|

Biography

The child who was later to be known as Takahashi Shōtei was born, Matsumoto Katsutaro,

in Mukoyanagiwara, Asakusa, Tokyo on January 2, 1871.

As a child, he was adopted into the Takahashi family, becoming known as Takahashi Katsutaro.

At the age of 9, he was apprenticed to his uncle, Matsumoto Fuko (1840-1923), with whom he

studied Japanese-style painting.

According to tradition, Fuko gave him his art name "Shotei" a variant of his own surname "Matsumoto".

The first Japanese character of their names is pronounced either "Sho" or "Matsu".

The child who was later to be known as Takahashi Shōtei was born, Matsumoto Katsutaro,

in Mukoyanagiwara, Asakusa, Tokyo on January 2, 1871.

As a child, he was adopted into the Takahashi family, becoming known as Takahashi Katsutaro.

At the age of 9, he was apprenticed to his uncle, Matsumoto Fuko (1840-1923), with whom he

studied Japanese-style painting.

According to tradition, Fuko gave him his art name "Shotei" a variant of his own surname "Matsumoto".

The first Japanese character of their names is pronounced either "Sho" or "Matsu".

At the age of 16, he went to work at the Imperial Household Department of Foreign Affairs, where

it was his job to copy designs of foreign medals, clothing, and other ceremonial objects.

In 1889, along with Terazaki Kogyo, he founded the Japan Youth Painting Society (Nihon Seinen

Kaiga Kyokai).

During his early years, he produced and exhibited original paintings and also worked as an illustrator

of scientific textbooks, magazines, and newspapers.

In 1892, he designed woodblock prints for a magazine published by Okura Shoten.

In 1896, he designed lithographs for the publisher Hokunkai.

During this time, he placed highly in competition at various industrial exhibitions.

Later, he worked for publisher Maeba Shoten (also known as Maehane Shoten) where he did line

drawing and color separations for reproductions of Ukiyo-e prints.

While working at Maeba Shoten, he became acquainted with Watanabe Shozaburo.

In 1907, he was recruited as the first artist for Watanabe Shozaburo.

He produced many original designs in the style of the Edo-era landscapes.

In 1921, he started using the gō "Hiroaki", however, many of his new prints continued to

display the "Shōtei" seal through the 1930s.

Up until the great Kanto earthquake, in September 1923, he produced as many as 500 print designs

for Watanabe.

Unfortunately, Watanabe's entire publishing operation was destroyed in the fires which followed in the

aftermath of the earthquake.

After the disaster, he produced 250 more prints for Watanabe, some of which were reproductions

of the older images lost in the fires.

In the 1930s, while still working for Watanabe, he also designed some oban (and larger)

prints for the publisher Fusui Gabo.

It seems that he had considerably more artistic freedom working for Fusui and

was allowed to explore areas which may have been off-limits under Watanabe.

At Fusui, he also acted as an editor for their Ukiyo-e reproductions.

Additionally, also in the 1930s, he produced almost 200 print designs for the publisher

Shōbidō Tanaka.

These included 12 mitsugiri-ban prints with approximately 180 prints in smaller sizes.

The picture to the right is of Shōtei and his wife Haru at Miyajima.

My research has revealed different dates for his death from various sources. Laurance P. Roberts'

A Dictionary of Japanese Artists puts his death in 1944. The 1951 Watanabe catalog says he died in April,

1945, at Hiroshima. Still another source suggests that he died on August 6, 1945, a victim of the atomic

bomb attack on Hiroshima, where he was visiting with his daughter. The truth of the matter is, according to

the family records of his descendants, he died on February 11, 1945 of pneumonia.

The Name Game

Shōtei

The name "Shōtei" is composed of 2 Japanese characters.

"Shō" is character #2212 in The Modern Reader's Japanese-English Character Dictionary, Second Revised

Edition, 1962, by Andrew Nathaniel Nelson. It means "pine".

"Tei" is Nelson's character #303. It means "cottage", "mansion", "arbor", or "restaurant".

The translation which feels right to me is "Pine Cottage".

The name "Shōtei" is composed of 2 Japanese characters.

"Shō" is character #2212 in The Modern Reader's Japanese-English Character Dictionary, Second Revised

Edition, 1962, by Andrew Nathaniel Nelson. It means "pine".

"Tei" is Nelson's character #303. It means "cottage", "mansion", "arbor", or "restaurant".

The translation which feels right to me is "Pine Cottage".

It is an ongoing source of confusion for some collectors that there was another Japanese

woodblock print artist, Watanabe Seitei (1851-1918), who sometimes used the name "Shōtei".

Seitei was well known for his kacho prints of birds and flowers.

Hiroaki

The name "Hiroaki" is also composed of 2 characters.

"Hiro" is Nelson #1563, which is translated as "broad" or "wide".

"Aki" is Nelson #2110.

Character 2110 has multiple pronunciations, each of which has somewhat of a different translation.

"Aki" means "empty", "vacant", "unoccupied", or "spare time".

So, "Hiroaki" might be translated to mean "wide open spaces".

The name "Hiroaki" is also composed of 2 characters.

"Hiro" is Nelson #1563, which is translated as "broad" or "wide".

"Aki" is Nelson #2110.

Character 2110 has multiple pronunciations, each of which has somewhat of a different translation.

"Aki" means "empty", "vacant", "unoccupied", or "spare time".

So, "Hiroaki" might be translated to mean "wide open spaces".

An alternate pronunciation for these characters is "Komei", which seems to be the preferred

pronunciation amongst current Japanese print dealers.

When pronounced "Komei" the second character is translated a bit differently to mean "clearness",

"shining", "eyesight", or "discernment".

So, "Komei" might be translated as "broad clear view", which is certainly a better fit with my

image of this artist.

Rakutei

There were quite a few prints attributed to Shōtei in the 1936 Watanabe catalog which were

sealed "Rakutei".

You can read all about why I think that Rakutei is not a separate artist, rather just another go of

Shōtei, at the Rakutei artist's page.

There were quite a few prints attributed to Shōtei in the 1936 Watanabe catalog which were

sealed "Rakutei".

You can read all about why I think that Rakutei is not a separate artist, rather just another go of

Shōtei, at the Rakutei artist's page.

Kakei

In the early days of Watanabe's shin hanga experiment, there were quite a few prints produced under

the seal of an artist named "Kakei". There is absolutely nothing known about this artist except

that his work was remarkably similar stylistically to the prints sealed "Shōtei".

I am convinced that "Kakei" was yet another go of Takahashi Shōtei, and have written

an article showing pictures of his work to defend

my point of view.

San Ji Sai

Tosh Doi, a shin-hanga expert from Tokyo, has pointed out that the characters to the left

appear above the artist's seals on prints O-1, O-2, O-5, O-9, O-27, O-28, O-29, M-51 and others.

Tosh writes, "According to my speculation, this art name of 'San Ji Sai' implies or admires

'Three Nature of SNOW, MOON & FLOWER' especially on his special series of 'Setsugekka' prints.

I finally managed to read the third obscure kanji character as 'Sai' which is equal to the same

character as 'Ichi Ryuu Sai Hiroshige'."

Tosh Doi, a shin-hanga expert from Tokyo, has pointed out that the characters to the left

appear above the artist's seals on prints O-1, O-2, O-5, O-9, O-27, O-28, O-29, M-51 and others.

Tosh writes, "According to my speculation, this art name of 'San Ji Sai' implies or admires

'Three Nature of SNOW, MOON & FLOWER' especially on his special series of 'Setsugekka' prints.

I finally managed to read the third obscure kanji character as 'Sai' which is equal to the same

character as 'Ichi Ryuu Sai Hiroshige'."

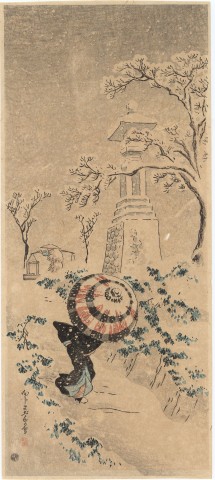

Shōtei prints O-27 through O-29 comprise a setsugekka set, representing snow (O-27),

moon (O-29), and flower (O-28).

This set of oban prints were produced in 1922, prior to the earthquake.

If the San Ji Sai signature had only appeared on these 3 prints, I would have said that it was a

notation for the setsugekka set, and not an art name.

However, it also appears on multiple post-earthquake prints.

Therefore, it must be an art name and is included here.

Watanabe and Shōtei

In 1902, at the age of 17, Watanabe Shōzaburo found his life's calling. When the pawn shop where he

was previously employed went bankrupt, he fell into a position in a branch store, in Yokohama,

of the ukiyo-e dealer Kobayashi Bunshichi.

Infatuated by this new world, he was very quick to become a connoisseur of ukiyo-e.

One of his responsibilities was to oversee the reproduction of Hiroshige and Harunobu prints from the original blocks.

In 1906, Watanabe left Kobayashi to start his own business as a print dealer and publisher.

By this time, he was very familiar with the extraordinary demand for ukiyo-e from collectors in

the United States and Europe.

The established way to supply this demand was to reprint editions from old blocks or to

recarve fresh blocks to reproduce the old images.

In 1907, he decided to try producing new images, in the ukiyo-e tradition, for export to the West.

Takahashi Shōtei was the first artist to produce images for Watanabe under this experiment.

His early shin hanga (new prints) were small format landscapes, stylistically reminiscent of Hiroshige.

They used the traditional ukiyo-e production methods of working from hanshita, where the artist first

designs the keyblock and then works with the carvers to design the color blocks.

This is very different from the method of carving blocks from artists' finished paintings, which had

become prevalent in the Meiji period.

Under the hanshita method, the artist is truly a print designer, with more control over

the intermediate processes and therefore more control over the finished product.

Since Takahashi had considerable experience as an illustrator for publication, and also having managed the

technical side of reproducing ukiyo-e restrikes, producing a hanshita

to initiate the print development process would be a natural thing for him to do.

Most of the subsequent shin hanga artists in Watanabe's circle produced finished paintings which

were then converted to prints by the artisans under the careful control of Watanabe himself.

Shōtei's prints were well received, predominantly by tourists and Western collectors, hungry for

a nostalgic reminder of the "old" Japan which was rapidly disappearing. They were a commercial

success.

In the period between 1907 and the earthquake in 1923, Shōtei produced some 500 prints, almost all of which

were smaller than oban in format.

There were only 11 oban prints produced prior to the earthquake (catalog numbers O-19 through O-29).

Watanabe considered oban and larger prints to be "high class colour prints" while smaller format

prints were considered commercial "tourist prints".

Prior to the earthquake, Kawase Hasui (whose first work for Watanabe was in 1918) had produced more than 100

full size prints; Itō Shinsui (who started in 1916) had produced 40.

Why was Shōtei, who had been working for Watanabe since 1907, relegated to the commercial side of the

business?

The common wisdom is that Watanabe considered Shōtei's work to be too "old fashioned" to be in tune with his

vision for creating a new genre of modern woodblock prints.

Looking at the 29 oban prints which were ultimately designed by Takahashi for Watanabe and the 23 which

were designed for Fusui Gabo, I have a lot of trouble accepting this explanation at face value.

The work speaks for itself.

It was not because of any shortage of personal artistic ability that Shōtei was limited to producing the

backward-looking art, which had become so commercially successful.

It seems clear that Watanabe assigned him a role to play and wouldn't allow him to leave that role.

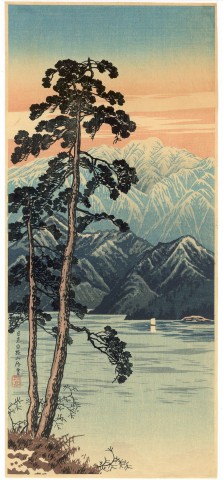

Rising above Watanabe's expectations of mediocrity, Shōtei designed absolutely stunning prints like this

one on the left.

But why? Why did Watanabe attempt to keep Shōtei down while, at the same time, nurturing the efforts

of Hasui, Shinsui, Shiro, and the others who became the stars of the shin hanga movement?

There is no documentation of which I am aware to help in answering this question.

Watanabe Shōzaburo was a strong-minded businessman who ran a tightly regimented organization.

When one mixes such structure with a creative pursuit (i.e. the production of art), it is inevitable

that creative boundaries will be rigidly esatablished and enforced.

Each member of Watanabe's team had a job to do and was expected to perform that job, without questions.

Within such an environment, there would need to be an overseeing presence to coordinate the efforts.

This person would ultimately have a considerable amount of artistic control over the final product.

Watanabe took on this job, and fancied himself as a designer of prints.

Since Shōtei had a history of acting as print designer, by virtue of using the hanshita

method of print development, he usurped Watanabe's "rightful" position.

However, since Watanabe had his hands full, acting as designer for the "high class" prints,

he allowed Shōtei to keep designing their financially successful line of commercial prints.

Takahashi was content to play this role as defined by Watanabe and their relationship was long-standing

and, presumably, mutually beneficial.

Although some of the points in the preceding paragraphs are my opinions based on conjecture,

here are some historical facts which seem to support them:

- In the 1936 catalog, unhampered by any modesty, Watanabe wrote, "Because I am the designer and

supervisor over the artist, engraver and printer, I have gotten an idea to have my seal on an ideal

art wood-cut print when it is made." By "ideal art wood-cut print", he was referring to oban

size prints.

- In 1936 and 1937, Watanabe published 2 prints ("West Park, Fukuoka, sunset" and "Lake Kawaguchi") which were

designed by him from photographs. Artist credit was given to Watanabe Koka, "Koka" being his go.

- Both Hiroshi Yoshida and Hashiguchi Goyo, after having Watanabe publish their first prints (9 for

Yoshida; 1 for Goyo), left to take control over their own hanga production. Neither one was

comfortable working within Watanabe's organization.

- Robin Devereux's excellent article

comparing some of Kawase Hasui's prints and the original watercolors from which they were designed

shows very clearly the extent of Watanabe's influence, as designer, on the final product.

In addition to the limited quantity of oban "high class colour prints", the mitsugiri-ban

and chuban "commercial" format prints of Takahashi Shōtei leave us a rich artistic legacy.

|