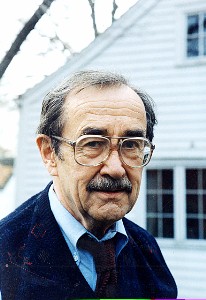

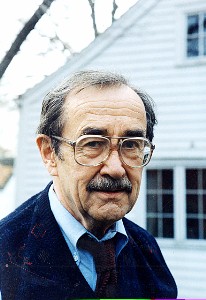

Robert O. Muller (1911-2003)

Robert O. Muller ("Please, call me Bob.") was the ultimate shin-hanga collector:

the right person, in the right place, at the right time, with ample means to pursue his passion.

Robert O. Muller ("Please, call me Bob.") was the ultimate shin-hanga collector:

the right person, in the right place, at the right time, with ample means to pursue his passion.

His extensive collection of Meiji, Taisho, and Showa era prints is the finest ever accumulated.

It has been documented in the books

Ukiyo-e Masterpieces in Western Collections: the Muller Collection (1990) and

The New Wave: Twentieth Century Prints from the Robert O. Muller Collection (1993).

Now that he has passed on, this rich legacy is available for posterity through his bequest of

the core of his collection to the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery of the Smithsonian Institution,

in Washington, DC.

Chronology

- October 5, 1911: born in Pelham, NY.

- 1929: graduated from The Gunnery, a college preparatory school in Washington, CT.

- 1934: received a bachelor's degree in history from Harvard University.

- Early 1940: purchased the assets of the Shima Art Company and founded the Robert Lee

Gallery in New York City

- February 3, 1940: married Inge. The newlyweds went on a honeymoon trip to Japan and China.

- December, 1941: (after Japanese invasion of Pearl Harbor) closed business premises

and put all of the print inventory into storage.

- 1941 to 1952: Inge gave birth to 4 daughters and a son.

- 1942 to 1945: worked at Pfizer pharmaceutical company in the lab where the "wonder drug",

penicillin, was being produced for the war effort.

- 1946: moved to Newtown, CT, having purchased an old house on about 20 acres. Re-opened

the Robert Lee Gallery in Newtown.

- 1950s and 1960s: sent traveling exhibitions of prints to colleges all over the country

and took orders for print sales.

- 1963: bought and ran Merwin's Art Shop in New Haven, CT.

- 1985: handed over management of Merwin's Art Shop to his son Robert L. Muller.

- April 10, 2003: passed away from Parkinson's disease. Up until his death, he continued to

accumulate prints and other Japanese art for his collection.

Link to

a scan of an obituary from Antiques and The Arts Weekly

My Visit with Bob Muller

Making Contact

During the summer of 2001, I started building the Shotei.com website and my catalog of the printed

works of Takahashi Shôtei.

I pored through books, sales and auction catalogs, on-line galleries, and other resources to gather

images of Shôtei's work.

One of the books was The New Wave which has 11 photos of Shôtei prints along with tantalizing

references to other prints from some of the "same series" which were in the Muller collection.

My cataloging efforts were well received by members of the hanga community.

Many people communicated to me their thought that it was long overdue that the work of this artist

be documented.

I received lots of images to be cataloged and lots of helpful advice about where I might find others.

Hans Olof Johansson, who runs the

Ukiyo-e: The Pictures of the Floating World website,

suggested that I try to get access to the Muller collection in order to get pictures of some of the prints

for which I hadn't yet found images.

He suggested that Jane Allinson, of

Allinson Gallery, Inc., a good friend of Mr.

Muller, might be able to help me to make contact.

Jane was most helpful in getting the two of us together, and I will always be very thankful

for her efforts.

I first spoke with Bob Muller, by telephone, in September, 2001.

He was quite pre-occupied with arrangements for his gala 90th birthday party and suggested that I get in

touch with him afterwards, in mid-October.

The second time that we spoke, he invited me to come for a visit and offered to let me stay in his

guest quarters.

He told me that he has always been very happy to make his collection available to assist people with

their research.

My Visit

I arrived at the Muller residence in Newtown the morning of November 10.

It is a very old New England home, originally built as an inn as early as 1690, but not

any later than the beginning of the 1700s, with the rooms arranged around a

central chimney structure, each room having originally had its own fireplace.

As a former carpenter, I was very impressed with the hand joinery, the post-and-beam construction,

and the massive oak floor boards held down with square nails.

Mr. Muller was a very gracious host.

After showing me the house and guest quarters, he sat me down to feed me and very quickly

let it be known that I was to call him Bob.

I expected to see lots of woodblock prints on display, but was surprised to find almost none,

although the house was packed with an eclectic blend of other objets d'art.

When asked about this he gave two reasons: "If I saw them all the time, I wouldn't appreciate them."

and "With open fires in the fireplaces, there is a lot of soot in the air."

After a short time, he said, "Let's go look at my pictures".

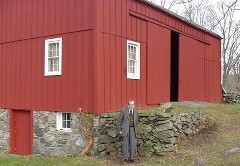

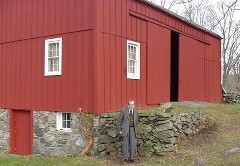

He asked me to wash my hands, and then we walked across the road to an old red barn, the home

of the famous Muller collection.

The main floor of the barn is divided into 3 separate rooms, 2 of which house the collection

of woodblock prints.

The third room was designed for hanging and viewing Bob's extensive collection of

Japanese scroll paintings.

After a short time, he said, "Let's go look at my pictures".

He asked me to wash my hands, and then we walked across the road to an old red barn, the home

of the famous Muller collection.

The main floor of the barn is divided into 3 separate rooms, 2 of which house the collection

of woodblock prints.

The third room was designed for hanging and viewing Bob's extensive collection of

Japanese scroll paintings.

The walls of the rooms housing the print collection are lined with safes and storage cabinets,

each of which has shelves built in.

On the shelves were clam-shell portfolio boxes, within which were the prints, each sandwiched

between 2 layers of museum board.

Bob had personally mounted each of his prints, cutting a window in the top layer of mat board.

Considering that each box contained about 25 prints, and each storage unit contained maybe 16 boxes, and

that there were perhaps 20 safes or cabinets distributed throughout the 3 rooms, I was totally overwhelmed.

Later, he told me that there were still quite a few prints that he hadn't yet gotten around to

mounting. Yikes!

The first box we looked at was labeled "Goyo and Shinsui".

It was an oversized box containing large format bijin-ga.

As we were looking through the prints, I was very impressed with the pristine state of each

print.

Halfway into the box, I was surprised to find some original pencil drawings by Hashiguchi Goyo.

This was shin-hanga heaven, indeed!

Of course, the business at hand was to get pictures of the Shôtei prints.

He said that he had 2 or 3 boxes of those.

I set up my digital photo equipment in the painting viewing room and proceeded to capture

33 images which hadn't yet been added to the catalog.

Mission accomplished!

Over the day and a half that we spent together, we had lots of conversations about the

"old days" and the people that he got to know in the shin-hanga world.

I'm going to share some of his insights in the next section of this page.

Bob told me, "The thrill of the collecting game is in the hunt".

Here he was, at the age of 90, still actively acquiring prints.

Bob was the constant target of dealers and museums who wanted to get a piece of his collection,

but, as an accomplished hunter, he wasn't interested in being hunted.

He seemed relieved and excited to find a fellow enthusiast whose motivations didn't include acquiring

some of his prints.

I left in the early afternoon of November 11.

My flight back home wasn't for another few days, but I felt that I had imposed upon his time enough.

Bob was in poor health and very frail.

My visit seemed to be wearing him out, so I cut it short.

I think that he was both disappointed in my departure and relieved that he was going to get a nap.

In saying our good-byes, he invited me to come back again, sometime.

Unfortunately, I didn't.

Bob Muller was an exceptional gentleman, a gracious host, and the most accomplished connoisseur

of shin-hanga that the world has known.

I feel privileged and very lucky to have been allowed to spend some time with this unique man.

Various Insights and Recollections

During the time that we spent together, we had lots of conversation.

I spent some time both evenings taking notes of what he had said.

There are lots of insights and recollections to share, so here they are, in no particular order:

- Family background: Bob was a direct descendant, through his mother's side,

of the German immigrant who founded the Pfizer pharmaceutical company.

- Early years of collecting hanga: As a college student in the early 1930s,

walking down a city street, a Hasui print in the window of a gallery caught his attention.

He bought that print and found his passion.

Throughout his college years, he regularly spent his entire allowance on prints.

His mother was critical of this and quite vocal, "How come you're throwing away your money?",

she would ask.

No matter, Bob persisted in his pursuit of prints.

When a family friend told her to be "thankful he's not spending it on booze and chorus girls"

like some of his contemporaries, peace was restored.

Later, during World War II, he got similar feedback: "Poor Bob, having thrown away his money

on that Jap print trash!"

- Shima Art Company: Shima was a New York City based distributor and "publisher"

of ukiyo-e reprints and shin-hanga.

It was founded by E. T. Shima who died. Mrs. Shima re-married a man named Mr. Sumii, who ran the

business.

Bob became a regular customer.

Shima would commission entire runs of prints from the Tokyo publishers such as Watanabe

and Nishinomiya, often having their own seal imprinted on the prints so commissioned.

When the Tokyo publishers either wouldn't or couldn't supply them, Shima would have knock-off

blocks carved by a Tokyo bookstore/publisher and publish their own facsimiles of the popular

designs.

In early 1940 (probably prior to the honeymoon trip to Japan), Mr. Sumii decided to sell

the business to Bob.

Bob said, "I gave him a check and he gave me the keys."

The inventory of the Shima company greatly enhanced the growing Muller collection.

During the war, the Sumiis were deported to Japan.

The day that they were to leave on a ship from New York City, Bob walked them to the boat,

helping with their luggage.

This was a very public statement of support for some friends who happened to be of a race

and nationality which was both disliked and distrusted at the time.

Back in Japan, Mr. Sumii became very successful in real estate.

Over the years, Bob and the Sumiis remained good friends and had many visits.

- Relationships with shin-hanga personalities: Much has been made about the "deep and lasting friendships"

between Bob and the Watanabe circle of artists which started during his honeymoon trip

to Japan in 1940.

Nothing could be further from the truth!

The picture to the right proves that Bob did meet some of them, but his description of the

meeting sheds a completely different light:

"The only reason those artists were there is because Watanabe made them.

Hasui spoke no English and made absolutely no effort to communicate.

Shinsui was not friendly and treated us like a couple of tourists.

Shirô was considerably younger than the others and treated by all the others as an inferior."

Bob never really got to know Watanabe Shozaburô, but did most of his communications

through Watanabe's assistant.

He described Watanabe as a very tight, controlling, dominant personality.

When I read my

essay on the relationship between Shôtei and Watanabe

to Bob, he told me that my analysis rang true to him.

However, Bob did become a close friend to the print and book publisher Nishinomiya Yosaku.

He was a house-guest on several trips to Tokyo in Nishinomiya's Victorian style home.

As a westerner, Bob was provided with a bed.

- Pearl Harbor and WWII: When Bob heard about Pearl Harbor, he went to the

store and removed all Japanese stuff from the windows.

He said, "If I didn't, all the enraged drunks would have trashed the place."

The store was closed, and all of the inventory was placed into storage.

The onset of war gave Bob a serious conflict: "All of my relatives were German and all

of my friends were Japanese".

While he wasn't about to be drafted, because of health reasons, his age, and being a father,

he also wasn't about to sign up for the military service because of his conflict.

Therefore, he set out to find a job doing essential war work.

After a couple of false starts, he found a job in the family business, Pfizer, in the production

lab where the new "wonder drug" penicillin was being produced.

Penicillin was discovered more than a decade earlier, but it was not practical to produce

it until Pfizer pioneered a fermentation process.

Bob told me "I was able to hold the total day's production of penicillin in my hands. We had

to be very careful. This drug was saving lives. If we ruined some, that meant people were

going to die."

- Selectivity: It's important to point out that the Muller collection

is a statement of Bob's selectivity.

He had a strongly subjective eye for evaluating art.

He bought lots of what he liked and turned his back on what he didn't like.

In addition to Japanese prints, I saw Japanese scroll paintings, raku pottery, both African

and Chinese wood carvings, and other prints, drawings, and paintings of all genres.

During our conversations, I asked if he had any prints by Tsuchiya Kôitsu or any

crepe paper books published by his friend Nishinomiya.

I have small collections of both of these.

In both cases, he surprised me with a strong "No".

He said he didn't like Kôitsu's work because his lines were too strong (I'm still not

sure what he meant by that.)

Regarding the crepe paper books, he said that Nishinomiya had shown him some of those, but since they

were for children, he wasn't interested.

- Sense of humor: Bob had a very keen sense of humor which came through during our

conversations in many different ways.

At one point, we were looking at a scroll painting which had some calligraphy at the top and

a painting of a crab below.

The crab was beautifully done in sumi with a minimal number of strokes.

Bob asked me if I would like to know the translation of the calligraphy above. I said that I would.

Bob: "It says Joe's Diner, tonight's special: soft shell crabs".

Bob's house was obviously very old, but the plaque affixed next to the door read, "Built in 1493".

When I saw that, I asked him if he had acquired the house from the Columbus estate.

He said that Columbus had built the house to keep his men busy, because if they weren't kept busy

they would have gotten into trouble with the Indian women.

With a gleam in his eye, he explained that most people accept that date at face value.

The Future of the Muller Collection

Bob indicated that he was quite often contacted by dealers looking for inventory and museums looking for donations.

Bob would tell the dealers that he wasn't interested in selling his prints.

With the museums, he was a bit more kind, telling them that they were "going to need some live sponsors."

During my visit, I felt like I couldn't ask the burning question, "What are your plans for your collection after

you're gone?". It was none of my business.

In May 2003, at the reading of his will, the art world was pleasantly surprised to find that Bob had "left the

Smithsonian Institution his collection of more than 4,000 Japanese color prints".

Click here for an Associated Press news

article about the bequest.

Click here for a public relations statement from

the Smithsonian.

In August 2003, The Asian Collection, an on-line print auction, offered 291 prints from the Muller collection.

Their notice of the auction read:

"This is a Special Auction featuring only prints from the estate of a world famous collector and dealer of

20th Century Japanese prints.

The Robert O. Muller Collection formed the basis for the reference "The New Wave" and the 4000 prints which comprised

the collection was recently bequeathed to the Smithsonian's Arthur M. Sackler Gallery.

We are fortunate to have received on consignment a small group of prints that were liquidated as part of the estate.

Mr. Muller had many prints that were not in included in the Smithsonian gift.

The vast majority of the prints in this catalogue are in the Kacho-e (bird and flower print) category of the

Shin-hanga (new print) genre.

There are also a few traditional landscapes and a number of Sosaku-hanga (creative prints).

We hope to offer additional installments in the future."

|