|

Amongst hanga collectors, Frances Blakemore is best known for her 1975 book, "Who's Who in Modern Japanese Prints", which included biographical sketches and sample artwork for about 100 sosaku hanga artists. Her life and works are well documented in Michiyo Morioka's 2007 biography, "An American Artist in Tokyo: Frances Blakemore - 1906-1997". In 1937, as "Frances L. Baker", she had a brief involvement as a shin-hanga print designer, producing 2 print designs for the publisher Watanabe Shōzaburō. Watanabe's early collaborations with the western artists Fritz Capelari, Charles Bartlett, Elizabeth

Keith and Cyrus Baldridge were successful and are very well documented.

However, his 1937 collaboration with Frances was completely undocumented until recently, both here on Shotei.com, in 2002,

and more recently and more completely in Ms. Morioka's book.

Highlights of Her Life StoryFrances Lee Wismer was born on June 19, 1906 in Illinois. As she grew up, her mother, a former high school art teacher nurtured young Frances's artistic talents. In 1925, she enrolled at the University of Washington, in Seattle, as an art student. Because it was necessary for her to work to support her studies, it took her 10 years to graduate. Frances made her living mostly in the arts, both teaching and creating. During her extended collegiate stay, she became well known and respected in the Seattle arts community. By the time she graduated, she was a well-rounded artist with both an academic background and an abundance of hands-on practical experience. The summer of 1935 was a watershed few months for Frances. She graduated from the university, married Glenn Baker, a graduate student in English literature, and the newlyweds quickly booked one-way passage to Japan, where Glenn hoped to find work as a teacher. Upon arrival in Tokyo, Frances quickly became enamored with the Japanese culture and aesthetic sensibilities. She must have gotten lots of attention in pre-war Tokyo as an American female working artist.

In the late 1930s, the political situation in Japan got increasingly uncomfortable for Westerners living there. Finally, in July, 1940, Frances left Tokyo and sailed to Honolulu where, with her characteristic enthusiasm, she became enchanted by the Hawaiian culture and landed commissions for her artwork. Frances watched, in surprise and horror, as the Japanese war planes flew over during the attack on Pearl Harbor. Life in Hawaii changed for all residents, overnight. Frances worked for a while as a wartime postal censor until June, 1944 when she went to work for the Office of War Information as an artistic designer for propaganda leaflets. Her efforts in psychological warfare were featured in this episode of the "History Detectives" television program. Millions of copies of Frances's leaflets, aimed of undermining Japanese popular support for their military dominated government and its war efforts, were dropped on Japan and its territories toward the end of the war.

During the immediate post-war years, Frances became close to Thomas Blakemore, another Japanophile whom she had met in Honolulu. Thomas was an attorney who had come to work for the US Government as part of the Japan Occupation, helping to rebuild the Japanese legal codes. Thomas and Frances married in 1954. They lived and worked in Japan until 1988, a time marked by many adventures, professional and artistic accomplishments, and the pursuit of various interests. In 1988, Frances and Thomas moved to Seattle, where they spent the final years of their lives. Thomas passed away in 1994; Frances in 1997. In Seattle, they created their gift to posterity, the philanthropic Blakemore Foundation dedicated to promoting American studies of Asian languages and arts. The above section on the highlights of Frances's life is a brief and inadequate summary.

For a much more complete exposition of the life of this fascinating artist, I suggest you get your hands on a copy of

"An American Artist in Tokyo: Frances Blakemore 1906-1997" written by Michiyo Morioka, published in 2007 by

The Blakemore Foundation, and distributed by University of Washington Press.

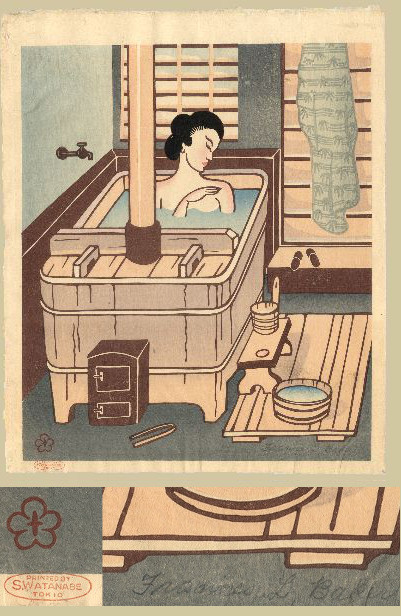

Frances's Collaboration with Watanabe ShōzaburōUnfortunately, in Frances's archived papers, she left no trace of the details of her relationship with Watanabe. The 2 prints which came out of their collaboration, in 1937, leave some mysteries which I find intriguing, but can only guess about their explanations and/or significance.Japanese Bath The printed area of the bathtub print is 27.4 X 22.6 cm.

It is signed in the lower right corner "Frances L. Baker", in pencil.

The printed area of the bathtub print is 27.4 X 22.6 cm.

It is signed in the lower right corner "Frances L. Baker", in pencil.

I'm intrigued by the 2 seals in the lower left corner. The five petal flower with the cross in it looks a bit like the inventory number seal of print S-4 in the Shōtei catalog, with the Japanese number "ju" which is "ten". However, the horizontal stroke of the cross inside the flower seal on this print is too short to read the character as a "ju". That seal has not been seen on any of Frances's other works. With the above exception, on a pre-quake Shōtei print, I've never seen that seal used by Watanabe. So, the significance of that seal is a mystery. The oval Watanabe seal also raises some questions.

I've never seen this format of seal before.

Why does it say "Printed by" instead of "Published by"?

Were the blocks carved elsewhere?

Did Watanabe operate merely as a printer for this print design?

If so, that would be quite a surprise, given Watanabe's inclination to control the entire process of print production.

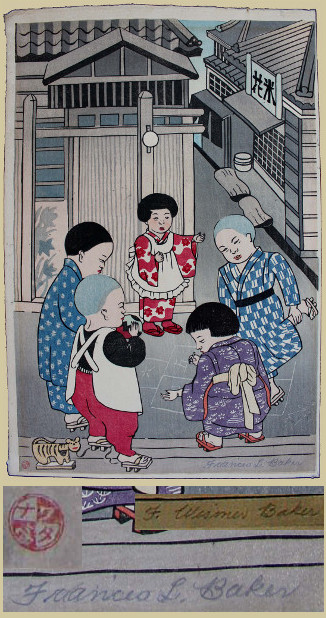

Children Playing on the Street The dimensions of the bathtub print are 35.8 X 23.6 cm (height X width).

It has the familiar 6 mm round Watanabe seal in the lower left corner.

The dimensions of the bathtub print are 35.8 X 23.6 cm (height X width).

It has the familiar 6 mm round Watanabe seal in the lower left corner.

The children, wearing geta sandals with elevated wooden platforms, are playing Hopscotch, with Japanese numbers written into squares on the pavement. The sign on the building behind the children and to the right has 2 Japanese characters, hana and yone, which translate roughly to "Flower Rice". In 1937, it was ambiguous whether Japanese characters were to be read left to right or the opposite way. If one reads those characters from right to left, they may be pronounced as the name "Yonehana". In modern Tokyo, there is a restaurant by that name in the Tsukiji Fish Market. The screen over the entrance to that establishment, and the fact that the children are playing during the daytime, may imply that the "Yonehana" in this picture is a restaurant, open only in the evening. That's my best guess. I have seen digital pictures of 2 copies of this print design. One of them is signed "F. Wismer Baker", while the other is

signed "Frances L. Baker", both in pencil in the lower right corner of the image.

A careful look at the one signed "Frances L. Baker" reveals that the print had originally been signed "F. Wismer Baker",

but part of the signature was erased and then modified.

It's a mystery why Frances would have changed the signature on one of her prints.

| |

| Home | Copyright 2014 by Marc Kahn; All Rights Reserved |

It is not known exactly how she got together with Watanabe, but the presumption is that they were introduced by a common friend.

Watanabe produced 2 of her prints in 1937, and that was the extent of their collaboration.

Unfortunately, no details about their working relationship have been recorded for posterity.

During this same time period, Frances produced some of her own woodblock prints, but mostly single block monochromatic productions.

It is not known exactly how she got together with Watanabe, but the presumption is that they were introduced by a common friend.

Watanabe produced 2 of her prints in 1937, and that was the extent of their collaboration.

Unfortunately, no details about their working relationship have been recorded for posterity.

During this same time period, Frances produced some of her own woodblock prints, but mostly single block monochromatic productions.