|

You’ve discovered the fascinating art of Japanese woodblock prints – breathtaking landscapes, beautiful women, fierce samurai, and more. Print reproductions are decorative, but actual woodblock prints are even better, and many are affordable, even on a small budget. So what do you do now? Here are five practical tips. 1. Now is a great time to start a collectionThe global recession has created a buyers’ market for most art. Many prints made during the lifetimes of Japanese master artists (called “original” or “early” impressions) are costly, but others – as well as quality 20th century “re-prints” - are readily available and affordable. If you have seen only reproductions (giclee copies or lithographs such as those in books), you’ll be amazed at how fine woodblock re-prints can be, as they were made the same way as originals. Owning woodblock prints allows you to see their beauty whenever you want. For under 100 USD, you can buy an entry-level original or several fine 20th century re-prints. There’s also the “thrill of the hunt” in finding a good print at a good price, researching an unidentified print (extensive information is readily available), and learning about the historical context the print reflects. 2. Don't worry if you can't read JapaneseOnce you’re familiar with the styles of the major artists, a design usually can be matched to reference images at specialized websites and books. These sources also have guides to artist signatures and seals (which changed over time). Other details such as publisher and year can often be deciphered by similar guides. Chinese-style calligraphy (with sharp angles like Western block letters) usually denotes artist, title and series, while free-flowing script (similar to cursive writing) is usually poetry. Some 20th century designs include English titles and/or artist signatures in Westernized phonetic translation (romaji). 3. Where to start

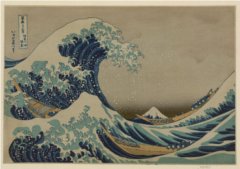

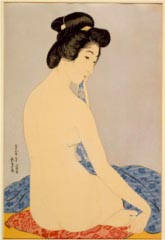

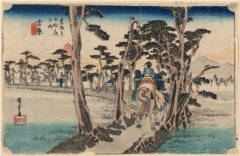

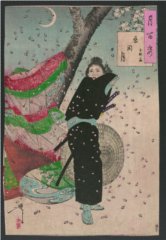

There are five main genres of Japanese prints: landscapes, beautiful women (bijin), actors and dramatic scenes, animals (usually birds) and flowers (kacho), and history (events, famous stories, wars, samurai). But a print may transcend genres, as when both a beautiful woman and a beautiful landscape are prominent, thus comparing the two (mitate). There also are specialized areas such as surimono (exquisitely printed designs in small editions for special occasions), shunga (erotic), and ehon (illustrated books), a relatively neglected area. While most artists focused on one or two genres, they could work well in others. This was due to their training, which included copying different genres in the Chinese (Kano) style, characterized in landscapes by bird’s-eye rather than Western vanishing-point perspective. (Kano-style prints found today are usually Chinese rather than Japanese.) Training also incorporated uniquely Japanese elements such as sharply defined clouds. Styles were influenced by earlier native artists, contemporary competitors, popular fashions, and (usually after 1800) Western elements. Most designs predating 1860 had soft colors; later, more garish inks were sometimes used. While most artists were based in Edo (now called Tokyo), others worked in Osaka, Yokohama, or Kyoto, and those cities had differing styles. After looking at many works by an artist, you will see his particular style, helpful to identify prints that lack signatures or are obscure designs. You’ll find you prefer certain artists or genres, but look at as many images as you can, because there’s always something new to discover and enjoy. 4. Look, look, lookThe Ukiyo-e masters each made thousands of different designs, and most of their successors also were prolific. Unfortunately, art museums seldom display prints, due to potential damage from light. (Their collections are normally only available to scholars.) But there are many excellent websites totaling thousands of images. Even if you have a wireless computer, you’ll want to obtain some reference books because many prints aren’t posted online. A convenient, encyclopedic book on Ukiyo-e is Richard Lane’s Images from the Floating World, while Helen Merritt’s two books are indispensible for modern prints. Although your local library will have only a few “survey” books, use interlibrary loans or book resellers to obtain specialized volumes.

Compare the print your’re considering to a known early impression. Examine the faces and calligraphy (they’re difficult to reproduce identically to an original and thus a quick check on quality). Also check color shading (bokashi) – lower-quality re-prints may lack the gradual shading found in good prints. If original details like an entire mountain range are omitted, the re-print is not high quality. Conversely, if the image includes unusual special effects like embossing (also called blind-printing or gauffrage), this shows the care used for a quality print.

Japanese publishers of quality modern prints and Edo/Meiji re-prints include Watanabe, Doi, Uchida, and Adachi. Although recent re-prints may be of similar quality, early impressions and older re-prints command higher prices, condition being equal. Re-prints lacking both publisher and date are often (but not always) of high quality. Subject is another identification help. For example, multiple artists often created different designs of particular Japanese landmarks, so recognizing the landmark narrows down the possibilities. Similarly, the date of a bijin image can be estimated by the woman’s hair style, and actors determined by their family crests on their kimono. Print size also is a consideration. Most Edo and Meiji designs were oban (roughly 10 by 15 inches; 24 by 37 cm), though more recent prints were sometimes in a variety of smaller sizes. Single (not multi-panel) images found larger than oban are likely reproductions. If a print is found in a size other than a known original, then it’s assumed to be a re-print. This does not mean it’s poor quality, but the smaller the re-print, the cheaper to produce and the more likely that details have been lost. Although engraving and lithography were occasionally used as early as the Edo era, until the 20th century very few woodblock artists also used these media, and even then there was little overlap. Until around 1925, it was very rare for woodblock artists to number, hand-title or hand-sign their prints in Western script (though some used hand seals). It was not unusual for earlier owners to write the artist’s name or the title on the print, so such inscriptions should not be assumed as in the artist’s hand except by comparison to a known original. Even on numbered designs (e.g. 27 of 100), it’s possible the design later became an unlimited edition, as nearly all Japanese prints before 1950 were. Sometimes differences between originals and re-prints are very subtle. For instance, a Meiji re-print of an Edo image may have used the same blocks, yet the value of the Edo impression will always be more than the re-print, condition being equal. In such cases, experts are needed. But as both the Edo and the Meiji print will have relatively high values, this is seldom a concern for the beginning collector. 5. Find good prints at good pricesBecause it’s always best to see a print in person, try to visit Japanese-specialty galleries and print shows near your home or travel destination. The focus is on higher-end images, but most prints will be priced close to market value, so they are neither great bargains nor grossly over-priced. In addition to having generally fair prices, many of these dealers are willing to advise new collectors and scout for desired prints. But retail specialty dealers have relatively limited stock and urban locales inconvenient for some collectors. In that case, you have four options: local retail sources, online specialized dealers and auctions, general-sales websites such as eBay, and Japanese re-print publishers. Each has pros and cons. Local retail sources include general art galleries, auction houses, and consignment and thrift stores, where both bargain and overpriced Japanese prints are occasionally found but, more often, reproductions and kitsch. If you visit such sources for other reasons, it’s worth a look for prints, but expect to find nothing. The internet has shifted most of the market to online specialized dealers and auctions, including sellers who have or formerly had retail galleries. Because these dealers understand the special issues of Japanese prints (e.g. photo close-ups of signature and verso), they’re always worth considering. Online sales have much less overhead than retail galleries, so prices are often good. And if your collecting interests change, online auctions can dispose of unwanted prints, though commissions and no-bids may take a toll. While eBay and similar websites offer a global market, they can be problematic for prints. First is sheer volume - an eBay search for “ukiyoe” returned more than 3,600 hits. Many sellers have poor photos, fail to note reproductions, and describe poor-condition prints as like the “car that grandma only drove to church.” Nonetheless, some good specialty dealers (including Japan-based ehon sellers) list on these sites, and feedback ratings are helpful in deciding whether to buy here. Your final option is Japanese re-print publishers. The pluses are good quality, new condition, and extensive catalogs. The main drawback is price, with most items costing at least 80 USD plus shipping, and recent printings (like cars) will not hold their value short-term. In addition to selling source, the impression quality and condition always should be considered. Some designs have variations in colors or other details (called “states”), but the details should be sharp. (Late printings from original blocks may show wear such as broken lines.) Unless the impression is very old, colors should be vibrant but not cloying. Colors on Edo-era impressions may inevitably deteriorate due to the inks used, but fading on later designs is never good.

Apart from condition, other factors in purchase decisions (and re-sale value) are artist and subject. As examples, prices for Yoshitoshi’s Meiji-era prints have grown in recent years, while Edo designs signed by Kunisada are often low-priced, likely because of his huge output, much of which reportedly was done by his students. Prints featuring Fuji or bijin are more appealing to most Westerners than those with actors or obscure Japanese motifs. As your collection grows, you can move beyond common re-print designs. You decide whether to frame your prints, but know that light and acidic framing materials are enemies. It’s best to use archival albums, and periodically rotate any framed prints. A final word about what every collector dreams of finding – a famous Edo-era original for a great price.

One dealer estimates that for every Hiroshige original still in existence, there are 10,000 re-prints.

That’s the bad news.

The good news for collectors on a budget is that nearly all the major design series of most master artists

are available in quality re-prints at affordable prices.

Happy collecting!

The author of this article, Brian Rasmussen, at the age of 20, received some prints originally given to his grandmother in 1912. While he always admired those prints, he has only gotten serious about collecting in the past year or so. He considers himself to be a beginner, and is surprised that there is not more material available written for the beginning collector community. This article reflects his commitment to share what he has learned and to help those who are beginners now and in the future. As of 2010, Mr. Rasmussen is 57 years old and a resident of Fairfax, VA. He works as a federal lobbyist. Thank you, Brian, for taking the time to share what you've learned!

| |

| Home | Copyright 2010 by Brian Rasmussen and Marc Kahn; All Rights Reserved |